Fixing Youth Sports in America: Part IV. Thinking Upstream

In the same manner as the previous piece in this series started — many of us acknowledge the ills of youth sports in America. And, we have bitched and complained about it a lot. And some have even offered possible solutions with the recognition of the challenges and barriers that come with trying to slow down this run-away freight train.

I have previously mentioned that one solution to solving the youth sports problem in America is money. To be clear, I mean funding towards appropriate resources to successfully disseminate and implement the “plans” and solutions that many organizations and people have drawn up.

But again, I will go back to the critical question that I asked the Collective Impact group at the annual American College of Sports Medicine meeting - ‘How, what and who will address the complex socio-cultural and behavioral aspects and the behavioral economics of changing (hearts and) minds and the U.S. youth sports culture at the individual and local level?’

This question fundamentally gets at the heart and soul of the “soft side” of human life – that is, what makes us tick behaviourally?

As I took on leadership roles as Director of Spartan Performance, Director of Coach Education & Performance at USA Football, and Head of Strength & Conditioning at IMG Academy, and also started thinking about widespread implementation of long-term athletic development across America, I changed my reading list from exercise physiology and sports science to books focusing on understanding the socio-cultural-behavioral aspects of human relationships and decision making. This led me to popular books like Ego is the Enemy, Predictably Irrational, Leaders Eat Last, Team of Teams, Braving the Wilderness, etc.

Along the way, one book that I found highly relevant was Upstream by Dan Heath. This is the third book from the Heath brothers (Chip is the sibling) that has shed light onto creating change in communities or organizations – exactly what we are trying to promote with LTAD (and Collective Impact). Thus, I wanted to take the opportunity to share a few key points in this fourth piece aimed at fixing youth sports.

Jacket Covers

Before I actually start reading a book, I’ll give it “a walk around and kick the tires”. I usually start with reading the jacket cover. The jacket cover is like an abstract of a research article. And the first few sentences on the inside cover of Upstream say a lot and really caught my attention.

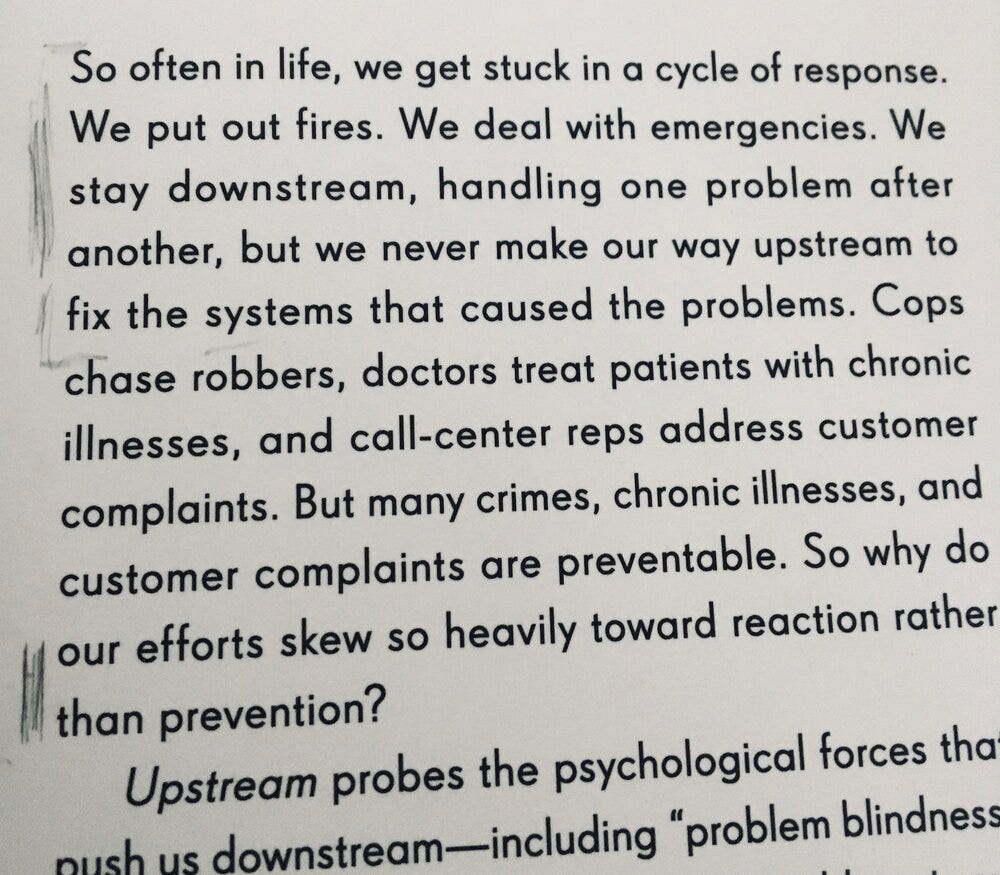

Indeed, we are often reactive, instead of proactive, when it comes to issues of youth sports. We seem to always be putting out fires and dealing with last minute emergencies. As pointed out in the above excerpt and throughout the book, there are countless examples from business to public health and beyond. And in youth sports, we complain that kids cannot skip or catch. Or that they have poor (place skill here, i.e. throwing) mechanics. Or that they don’t know the game well enough. Or that the coach does not know anything. Or that the parents are a big-time pain in the ass!

But yet, we stay downstream. Why?

Is it because that when you spend years responding to problems you overlook the fact that you could be preventing them (p. 2)? Is it because when we create organizations (schools, teams, clubs) that we force people to be myopic and just focus on the organization’s mission (p. 4-5)? Is it because downstream efforts are narrow, fast and tangible, while upstream efforts are broader, slower and hazier (p. 9)?

The 3 Barriers to Upstream Thinking

In Section 1 of the book, Heath writes about the 3 barriers to upstream thinking:

1. Problem Blindness – “I don’t see the problem”

2. A Lack of Ownership – “The problem is not mine to fix”

3. Tunneling – “I can’t deal with it right now”

Problem Blindness: I don’t see the Problem

The first example given for Problem Blindness is directly related to sport. The problem was the rash of hamstring injuries being experienced by the New England Patriots. The problem blindness was the traditional thinking of “it’s just part of the game, and you can’t do anything about it” – the belief that negative outcomes are inevitable. And maybe this is akin to “this is how we’ve always done it.”

Of course, hamstring injuries can be reduced with proper training, as occurred in this case. So often, to spark change we must contend with those with a fixed ‘that’s just how it is” mindset.

Here’s another great example for problem blindness. In 1998, the Chicago Public Schools high school graduation rate was 52%. The prevailing fixed mindset being “you either make it or break it”. Researchers from the University of Chicago found that they could predict which freshman would graduate and which ones would drop out with 80% accuracy. There were two key factors, and once focused upon, including shifting human resources – better teachers for freshman courses (read ‘better coaches at the youth level’)– the graduation rate (read ‘continued participation in sport’ or ‘a great experience in sport') shot to 78% by 2018.

Heath points out that this story of the Chicago Public School system has many overarching themes for success. He writes:

To succeed upstream, leaders must … …

Detect problems early

Target leverage points in complex systems

Find reliable ways to measure success

Pioneer new ways of working together

Embed success into systems to give them permanence

But first, leaders must awaken from problem blindness. You can’t solve a problem that you can’t see. Too often, we get habituated to the problem. If we walk into a room and hear a buzzing sound, five or 10 minutes later the buzz has receded into normalcy. What’s that loud buzzing sound that has become normalized in youth sport and athletic development?

Lack of Ownership: The Problem is not mine to Fix

In terms of Lack of Ownership, we have all been guilty of it at some time. Here’s a statement from the book that stands out – “upstream work is chosen, not demanded.” It’s chosen! You elect to do it. Why? Because you are in the best position to fix it and you stepped up to the plate. You are the LTAD champion in your community. A leader. Unless somebody leads, nobody will!

Tunneling: I can’t deal with it right now”

As for Tunneling (“I can’t deal with it right now”), we’ve all been there as well. I’m too busy. But if not now, when?

You are the right person and the time is now. Like my good friend and colleague Dr. Tony Moreno stated “the people who will make the biggest difference are not those who write the white papers or plans or those from the major organizations, but those who have the fewest initials behind their name.”

7 Questions for Upstream Leaders

As mentioned above, this upstream effort is going to take a leader, a grassroots community champion. And here are the 7 questions that Upstream Leaders need to consider.

1. How will you unite the right people?

2. How will you change the system?

3. Where can you find a leverage point?

4. How will you get early warning of the problem?

5. How will you know you’re succeeding?

6. How will you avoid doing harm?

7. Who will pay for what does not happen?

Get the Right People on The Bus… and in the Right Seats!

Getting the right people on board is so important. So many of us are passionate about best practices in youth sports or long-term athlete development and we want to conquer the issues, but we quickly realize that we cannot do it by ourself.

There are so many famous quotes about collaboration and teamwork versus solo efforts that it’s hard to pick one, but let’s go with this one -By building a collaborative team, you make people feel part of the solution and their voices heard. It also allows you to “surround the problem” (p.76).

However, you also want to be strategic in selecting core members. Plus, remember the “2 pizza rule” – a simple rule from Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos that maximizes effectiveness. The rule states that no meeting should be so large that two pizzas can't feed the entire group. Think about it. When you have a big group, some ideas get drowned out and often times nothing gets accomplished in these meetings or projects. This goes along with “too many cooks in the kitchen”. Ideally, about 5-8 people working as a collaborative team.

Rome was not built in a day – and if you want to re-build Rome, get up close to the Romans

It is important to remember that system change takes time (Rome was not built in a day). One key aspect of leveraging the system is to get close to the problem – that is, immerse yourself in the problem. Connect with coaches, parents, athletes. Immerse yourself in the organization. If you already don’t, you need to walk in the shoes of the end users. Learn to appreciate the full complexity of people’s lives (coaches, parents, teachers, kids) that are affected by the issues as well as the complexity of the systems in which they operate (p 132). More than likely, you are already doing this if you are reading this piece but perhaps widen your lens – think of all the layers of the onion (the “systems”).

Eyes (data), ears (people) and early warnings

How will you get early warning of the problem? First, collect data. And more specifically, data for the purpose of learning, not data for the purpose of inspection (p. 89). Remember, “data takes you away from philosophical insights. You move from anecdotal fights to what people are thinking (or feeling) to what is really happening (p.95).” With that said, it’s also important to keep in mind that “while technology can aid our early detection efforts, sometimes the best sensors are not devices, but people (p. 142)”. To anticipate problems, we need both eyes (data) and ears (people) in the environment (p. 143).

What counts as success?

Choosing the wrong short-term measures can doom upstream work (p. 160). There is another great sport-related example used in the book that highlights what Heath calls “ghost victories” (p 154)

“…imagine a long-struggling baseball team that is determined to remake itself a winner. Because that journey may take years, the manager decides to emphasize power hitting-especially more home runs-as a more proximate measure of success.. although your measures show that you’re succeeding, but you’ve mistakenly attributed that success to your own work. The team applauds itself for hitting more home runs but it turns out every team in the league hit more because pitching declined. In addition, the team doubled its home run production but barely won any more games. Furthermore, the pressure to hit more home runs led several player to take steroids, and they got caught.”

Again, choosing the wrong short-term measures can doom upstream work.

Respect the complexity of systems

So how can you avoid doing harm? Look beyond the immediate. Respect that systems are complicated. When you kill the cats, rabbits start overpopulating.

“Upstream interventions tinker with complex systems, and as such, we should expect reactions and consequences beyond the immediate scope of our work…. As you think about a system, spend part of your time from a vantage point that lets you see the whole system, not just the problem that may have drawn you to focus on the system to begin with’ (p.174)

Another aspect of understanding the complexity of the system is prompt and reliable feedback. Heath writes (p. 179) “consider navigation as an analogy: to travel somewhere new we need almost constant feedback about our location; we follow the arrow on a compass or the blue dot on Google Maps. Yet that kind of feedback is often missing from upstream interventions.”

It is also important to note that “whatever the plan you have is, it’s going to be wrong…. And if we aren’t collecting feedback, we won’t know that we’re wrong, and we won’t have the ability to change course (p.180)…. Because systems can’t be controlled but they can be designed and redesigned (p 188).”

Feedback loops spur improvement. But they must be in place. Allow opportunities for feedback from multiple stakeholders.

It’s Always about the Money: Paying for Upstream Efforts

Nothing is free in life. And with your plan will come the question – who will pay for it? Whether that be time or money.

Paying for upstream efforts ultimately boils down to 3 questions (p 201):

1. Where are there costly problems?

2. Who is in the best position to prevent the problem(s)?

3. How do you create incentives for them to do so?

In health care, Medicare spends a fortune paying for hospital visits that could have been prevented. The people best positioned to prevent some of those problems are primary care doctors. To incentivize primary care physicians, the Accountable Care Organization was established. One primary care doc said that this model, which includes spending more time with patients, transformed his practice – he became “more proactive than reactive”. The outcomes: happier, more satisfied patient care, healthier patients, and less overall health care costs.

We’ll pay $40k for insulin 💉but won’t pay $1000 to prevent it

🚑We’ll pay $20-50k for ACL surgery & rehab but ......🦵🏽🏋🏻

“an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” Ben Franklin— Joe Eisenmann PhD (@Joe_Eisenmann) December 22, 2020

The Spirit of Upstream Thinking

Let’s finish up in the spirit of LTAD and the spirit of upstream thinking with this final nugget of knowledge- “With some forethought, we can prevent problems before they happen, and even when we can’t stop them entirely, we can blunt their impact (p 231).”

Related

The Current Crisis in Youth Sports

Fixing Youth Sports in America: Part II - National Governing Bodies

Fixing Youth Sports in America: Part III - Collective Impact ... and the Elephant in the Room